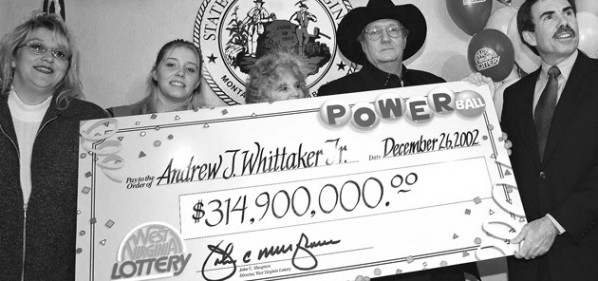

It’s a cliché to say that money can’t buy happiness, but in the case of Jack Whittaker, who won $314.9 million in the Powerball lottery in 2002, the story is a lot worse than that. In a story that feel like it was pulled from a Hollywood screenplay, Lottery Winner Jack Whittaker’s Losing Ticket by David Samuel in the December 12, 2012 issue of BusinessWeek, breaks down Whittaker’s misfortunes after winning the lottery.

Photo by Bob Bird/AP Photo

Samuel’s story on Whittaker is written very straightforward and journalistic style. There aren’t a lot of literary, poetic flourishes here (the story is for BusinessWeek, not The New Yorker, after all). But what stands out to me in this story is how much fine reporting is packed into the piece, and how well Samuel peppers the narrative with concrete, vivid details.

The opening two paragraphs are a great example of this:

Jack Whittaker, a 55-year-old contractor from Scott Depot, W.Va., had worked his way up from backcountry poverty to build a water-and-sewer-pipe business that employed over 100 people. He was a millionaire several times over. But when he awoke at 5:45 a.m. on Christmas morning in 2002, everything he’d built in his life held only passing significance next to a scrap of paper in his worn leather wallet—a $1 Powerball lottery ticket bearing the numbers 5, 14, 16, 29, 53, and 7.

Whittaker had purchased his lucky ticket, along with two bacon-stuffed biscuits, at the C&L Super Serve convenience store in the town of Hurricane on Dec. 24, 2002. That night, Whittaker went to bed thinking he’d missed winning the lottery by one digit—only to wake up on Christmas Day to find that the number had been broadcast incorrectly and the winning ticket was in his hand. “I got sick at my stomach, and I just was [at] a loss for words and advice,” he later remembered. When he returned to the convenience store on Monday, he quietly told the woman at the cash register he’d won. “No you didn’t,” she replied. “You’re not excited enough to win the lottery.”

Aside from some essential information: his age, where he was from, and what he did for a living, we also find out exactly when he woke up on Christmas morning, what kind of wallet he carried, the exact numbers on his ticket, what he ate the night before, the name of the store where be bought the ticket, and what was said between him and the woman at the register the next day. Most of those are small things, but they flesh out the scene. Sometimes it’s not great metaphors or turns of phrase that make writing feel alive, it’s the simple use of precise details.

Whittaker’s initial response and public statements show him to be generous and thoughtful about his good fortune: he donates a sizable part of his winnings to found two churches, set up a foundation for the needy, and even buys a new car and a house to the “biscuit lady” at the C&L. But the story quickly turns for the worse, with his family crumbling around him and his own behavior becoming wildly erratic and lawless. His teenage granddaughter, Brandi Bragg, with whom he was particularly close, also spirals out of control.

The heart of the story is a meticulously reported account of the many things that went wrong since the day Whitthaker posed with that massive pretend lottery check for the media. It goes from comical to disturbing to tragic.

And then the second part of the story shifts to Samuel’s efforts to track down and talk to the increasingly reclusive Whitaker. And here, the reporting is direct, but offers little elements of metaphor:

In the ten years since he became the wealthiest lottery winner in history, Whittaker has spoken rarely with the press. There have been reports that he’s broke. His name isn’t listed in the phone book, and none of his businesses—which include a bewildering variety of names and addresses—seem to be currently operating. At the rural address on the tax returns of the Jack Whittaker Foundation, there’s little more than a muddy lot with a few trailers and rows of used construction equipment. At the end of the lot, a small single-story building with a sign on the door reads “Please ring bell for assistance.”

In October, I rang the bell and waited in the rain. Through the glass of the door, I could see a photocopied color snapshot of a smiling blonde girl with hazel eyes, whom I recognized as Bragg. The plant by the front desk was dead, and judging by the leaves on the carpet, had been for a while. Around back a man in work clothes was sitting in his Jeep, waiting for the tank to fill up with diesel. “You won’t find him here,” he said. He offered a rough location for another Whittaker office, half an hour away.

Samuel’s description of the “muddy lot” where the Jack Whittaker Foundation exists today conveys a lot that he doesn’t have to say explicitly. And there’s no journalistic reason for him to mention the dead plant at the front desk and the fallen leaves on the carpet; they serve the story symbolically.

I enjoyed this story — it’s a superb piece of reporting — but I wish Samuel could have fleshed out the story a bit by talking with other figures in the story to get more of a sense of Whitthaker, stuff that wouldn’t show up on the police reports. I’d love to have heard from the Biscuit Lady, or one of the people at the many strip clubs he frequented, or someone who had been aided by his foundation. The story gives us a lot about the man, but it feels like we only get to understand him from a distance. Samuel makes it clear in the story that Whitthaker didn’t really want to talk to him. But as Gay Talese showed long ago, sometimes the best way to tell someone’s story it to talk to the people around them.

Samuel did a fine job here with limited access to the subject of his story. The reporting and storytelling is excellent, even if the story itself is a bit of a downer. He sprinkles the story with details and little bits of symbolism here and there to round out the edges of the piece. I’m not sure what to make of Whitthaker by the end of the story, but it has me thinking twice about how much better life would be if I won the lottery tomorrow.