2012 has been a horrifying year for guns: after the shooting of unarmed Trayvon Martin, the massacre at the cineplex in Aurora, Colorado, and the kindergarden shootings in Newtown Connecticut, Americans have refocused on the issue of gun violence.

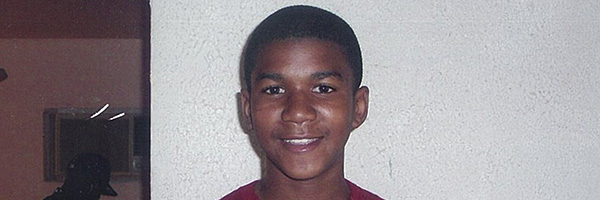

Travon Martin, family photo

Battleground America by Jill Lepore in the April 23 New Yorker takes a close look at the issue, underscoring the history and culture surrounding guns and the Second Amendment, as well as exploring the depth of the problem.

What makes Lepore’s story so strong is that it is viscerally close up in parts, but steps back and looks at the matter from a macro and historical level. It shifts between the personal and the policy sides of the story.

And the backbone of the story is the narrative of a single incident of a school shooting at an Ohio High School. As Lepore unravels the history and state of guns and gun violence in America, she dribbles out what happened before, during, and after one of too many gun massacres in America in recent years. With this, the bloody, personal toll of the issue is never lost on the reader, it feels urgent and horrifying:

At Chardon High School, kids ran through the halls screaming “Lockdown!” Some of them hid in the teachers’ lounge; they barricaded the door with a piano. Someone got on the school’s public-address system and gave instructions, but everyone knew what to do. Students ran into classrooms and dived under desks; teachers locked the doors and shut off the lights. Joseph Ricci, a math teacher, heard Walczak, who was still crawling, groaning in the hallway. Ricci opened the door and pulled the boy inside. No one knew if the shooter had more guns, or more rounds. Huddled under desks, students called 911 and texted their parents. One tapped out, “Prayforus.”

Almost as scary as the retelling of some of these incidents is the sheer numbers. She makes clear that this isn’t the problem of a few crazed loners, but a culture of guns and the deep proliferation of firepower across the nation. She lays out the facts about guns in America, putting the evidence on the table like a prosecutor:

There are nearly three hundred million privately owned firearms in the United States: a hundred and six million handguns, a hundred and five million rifles, and eighty-three million shotguns. That works out to about one gun for every American. The gun that T. J. Lane brought to Chardon High School belonged to his uncle, who had bought it in 2010, at a gun shop. Both of Lane’s parents had been arrested on charges of domestic violence over the years. Lane found the gun in his grandfather’s barn.

The United States is the country with the highest rate of civilian gun ownership in the world. (The second highest is Yemen, where the rate is nevertheless only half that of the U.S.) No civilian population is more powerfully armed.

As she delves into the history of the Second Amendment and the National Rifle Association, she, like Adam Winkler in “A Secret History of Guns,” (which I reviewed a week or so ago) she reveals that the notion that every American in entitled to own and carry as many firearms as they’d like is a relatively new idea. Far from the recent arguments from the N.R.A. that the Constitution has made gun ownership sacrosanct since the the founding of the nation, she shows that American mania for personal gun ownership has really been much more of a recent development, rising most dramatically in the 1970s.

Lepore even goes to a gun education class and takes some shoots at a shooting range herself, to get a sense of how it feels to fire a gun.

But the story keeps coming back to the human cost of guns. The story never veers too far away from the personal nature of the issue. And she does it with writing that is very personal and haunting. She never lets the reader forget how many innocent men and women have been murdered with guns, and that they all had names and lives that ended prematurely:

Here she grimly details one such group of victims:

They had come from all over the world. Ping, twenty-four, was born in the Philippines. She was working at the school to support her parents, her brother, two younger sisters, and her four-year-old son, Kayzzer. Her husband was hoping to move to the United States. Tshering Rinzing Bhutia, thirty-eight, was born in Gyalshing, India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. He took classes during the day; at night, he worked as a janitor at San Francisco International Airport. Lydia Sim, twenty-one, was born in San Francisco, to Korean parents; she wanted to become a pediatrician. Sonam Choedon, thirty-three, belonged to a family living in exile from Tibet. A Buddhist, she came to the United States from Dharamsala, India. She was studying to become a nurse. Grace Eunhea Kim, twenty-three, was putting herself through school by working as a waitress. Judith Seymour was fifty-three. Her parents had moved back to their native Guyana; her two children were grown. She was about to graduate. Doris Chibuko, forty, was born in Enugu, in eastern Nigeria, where she practiced law. She immigrated in 2002. Her husband, Efanye, works as a technician for A.T. & T. They had three children, ages eight, five, and three. She was two months short of completing a degree in nursing.

Ping, Bhutia, Sim, Choedon, Kim, Seymour, and Chibuko: Goh shot and killed them all. Then he went from one classroom to another, shooting, before stealing a car and driving away. He threw his gun into a tributary of San Leandro Bay. Shortly afterward, he walked into a grocery store and said, “I just shot some people.”

This won’t be the last lengthly examination of guns we’ll see, especially in the light of the Newtown tragedies, but it will still be one of the most comprehensive and well-written stories on the issue.